Level 2

4.1.1 Developing an Athlete’s Mindset

What is the Athlete’s Mindset

Involvement in sport is widely regarded as having many benefits, particularly for young people. In addition to health benefits that may flow from involvement in sport, junior sport participation can have many important social benefits such as developing life skills (e.g. communication, concentration, commitment)

- learning responsibility and discipline

- learning how to work with others in team environments

- learning to cope with success and failure

- developing a sense of community, loyalty and cohesion

- helping some gifted young people become aware they are role models for others.6

However, the extent to which a young person will experience any social benefit depends upon the experience that they have with their involvement in sport.

A successful athlete’s “mindset” can probably be characterized by three things:

- confidence in their ability to perform;

- understanding that losing is an inherent part of sport and that failure to achieve one goal doesn’t mean that the overall goal cannot be achieved;

- belief that if they “do the work” they can improve their performance.

Such a mindset can be immediately linked to some of the social benefits described above.

Coaches can accordingly enhance the “mindset” of their players in a number of ways.

Coping with Success and Failure

Both winning and losing are an inevitable part of sport. As a team sport, winning or losing (or success and failure) applies in the following contexts:

- the end result (winning or losing games);

- individual contests within a game (e.g. scoring or rebounding against an opponent);

- learning the skills and tactics of the games and being able to perform them in games.

Whilst it may seem that “winning” is very easy to cope with, there are a number of characteristics that the coach should still impart:

- respect for the opponent – the coach must ensure that the team shows respect for their opponent;

- winning can also bring the pressure of expectation of further success, which athletes may struggle to cope with.

Whilst winning a game should be celebrated, the approach to winning and losing should be the same – what does the team know need to work on to further develop?

“Losing” is an adversity that is unavoidable in sport. It may be in relation to a particular aspect of play (e.g. your opponent drives past and gets and easy shot), it may be the outcome of a particular game or it may occur off the court, such as not being selected for a team.

Athletes of course strive to win but the reality for almost all athletes is that they will lose just as many times, if not more, as they win. In losing, coaches should be prepared to acknowledge that the other team was better (at least “on the day”) and then identify areas for improvement and start to address those.

With this “mindset”, losing does not mean that a player or a team is “no good”, it simply means that another team was better, which may identify areas to improve. This is a positive message to give to athletes, who at the time of losing may and probably will have negative thoughts about their performance. If the coach can foster an attitude or mindset that after a loss that “I am not yet successful”, it can motivate players to continue to develop.

However, if the coach simply berates players for “lack of effort” or shakes their head in dismay “I don’t know how we lost that game”, their players are unlikely to see how the situation can improve. The coach must be both specific and realistic – simply saying “we’ll beat them next time” will soon ring hollow with athletes.

The “mindset” equally applies to when a team wins. A win does not mean that the team does not have areas to improve. Indeed, many times a team plays poorly but wins and on other occasions plays very well, but loses.

With an athlete’s “mindset”, players and coaches ultimately derive satisfaction from knowing the effort and improvement they have made and the level of expertise which they reach.

Losing is different to Failing

One way that coaches can help develop a player’s ability to “cope” with losing is to keep perspective of what the failure was. Only one team can win the championship, only one athlete wins the gold medal in a race. The coach should have other criteria by which the team, and each player, can evaluate their performance.

The criteria can then form an important part of identifying both improvement (which is a success) and in motivating the athlete to continue to strive to develop further. The criteria might reflect upon what they have learnt during the season, other statistics (e.g. reducing turnovers, shooting percentage, rebounding) or comparative to a rival particularly if they were easily beaten early in the season and became more competitive.

Most importantly, coaches must recognize that players will be understandably disappointed when they lose, particularly if they lose a championship game. Coaches should emphasize that disappointment is natural but should not affect the player’s overall self-esteem.

Taking Personal Responsibility

Coaches must foster an environment where players and coaches take responsibility for what they can control. If the coach blames the referees for a loss, how can they expect that players will take responsibility for their actions?

Instead, coaches should focus on what the team, and individuals, need to do better and the message must be positive – if individuals do better on each task, the team’s performance will improve.

Personal responsibility also comes from each player being accountable for the role that they have on the team. Coaches can enhance this by setting goals and then measuring whether or not they are achieved. Receiving this feedback, and accepting the role that they have, is an important aspect of an athlete’s mindset.

Long races are won by little steps

Most teams will want to win the championship, however the coach (and each player) must understand there are many smaller goals that need to be achieved in order to be in a position to win a championship.

This approach is both motivating (as the attainment of a goal is a great motivator to pursue the next goal) but also provides a basis upon which to judge success, in the event that the ultimate goal (championship) is not achieved.

As coach Bob Knight reminds us, “most people have the ‘will to win’, few have the will to prepare to win”. Focusing on each of the steps toward an ultimate goal will test whether or not the will to prepare to win exists.

Learning to train “hard”

One characteristic of elite athletes is how “hard” they practice – as Magic Johnson reminds us “with few exceptions the best players are the hardest workers”.

However, young players often underestimate what they can achieve. Their view is often limited by their own experiences up to that time and those of friends and family.

For example, if a student comes from a family where nobody has ever attended university, the student often will not believe that they can. They may hold this view irrespective of their school grades which indicate they could go to university.

Such limitations are perhaps most commonly seen when working with athletes on their fitness or conditioning. Ask an athlete to complete a physical task (e.g. sprinting full court) as many times as they can and most will stop running before reaching the point where they can physically run no more.

Some coaches will yell encouraging words at the athlete to extract as much effort as possible from the athlete, and this may work to some extent. Coaches must avoid making “threats” or negative remarks.

An elite athlete may not necessarily have any greater physical capacity than other athletes but what often sets them apart is that they are actually able to reach their capacity (or potential).

An important role for a coach is to help the athlete achieve more than what they initially thought they were capable of achieving. Setting realistic, but challenging, goals is important. As is breaking down a large goal, e.g. “I want to be selected to the national team,” into a series of goals that progress toward that.

There is no definitive measure of how “hard” an athlete trains, however it is influenced by both their level of “fitness” and also their mindset. When trying to improve the fitness of athletes the coach often has to change the athlete’s mindset.

Having players take their heart rate during training can give an indication of how “hard” they are working. To do this, have players count their pulse for 10 seconds and then multiply by 6 to get their heart rate.

A player’s maximum heart rate is approximately 220 minus their age. When players work “hard” they should be at 85% of maximum heart rate.

Humans are “pack” animals, simply meaning that we have the capacity for empathy and we generally prefer to be a part of a community. It is drawing upon this sense of wanting (or needing) to “belong” that coaches can use to help athletes to understand that they can work “harder”.

In the example above of the athlete being asked to run as many sprints as they can, irrespective of the coach “yelling” the following will usually get more effort from the athlete:

- other athlete’s encouraging them;

- an athlete running alongside them;

- playing “energetic” music (provided that it is music the athlete likes).

The power of human touch should also not be overlooked. When someone is upset, a friend will often comfort them by touching their arm or shoulder and this simple, physical connection will help the friend to feel better.

Similarly, a “high five” (clapping hands) between athletes or helping another athlete get up when they are knocked to the floor, can also be very effective ways for athletes to support each other.

It is common in basketball to see teams put “hands in” at the end of a time-out, however this is often half-hearted.

When it works best, is where the player’s make a connection with each other. Below are examples of activities a coach can use to have their athletes work together and support each other, helping each individual to “push” themselves to achieve a level above what they would by themselves.

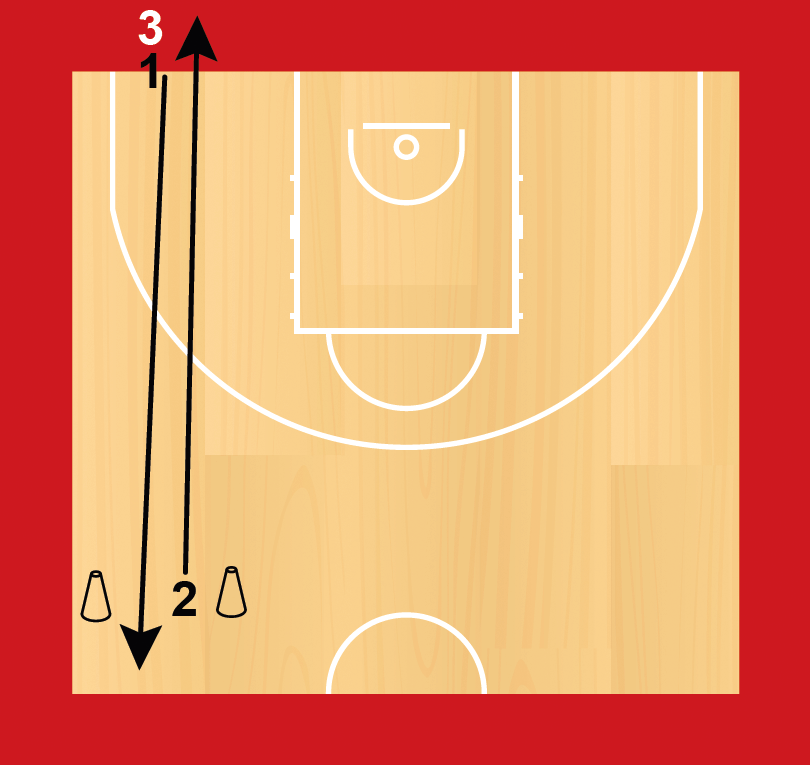

Relay 3

In groups of 3, athletes sprint a specified distance. They give their team mate a “high five” and that person then sprints the distance.

For longer distances, have 4 athletes involved, so that two are running and two are resting.

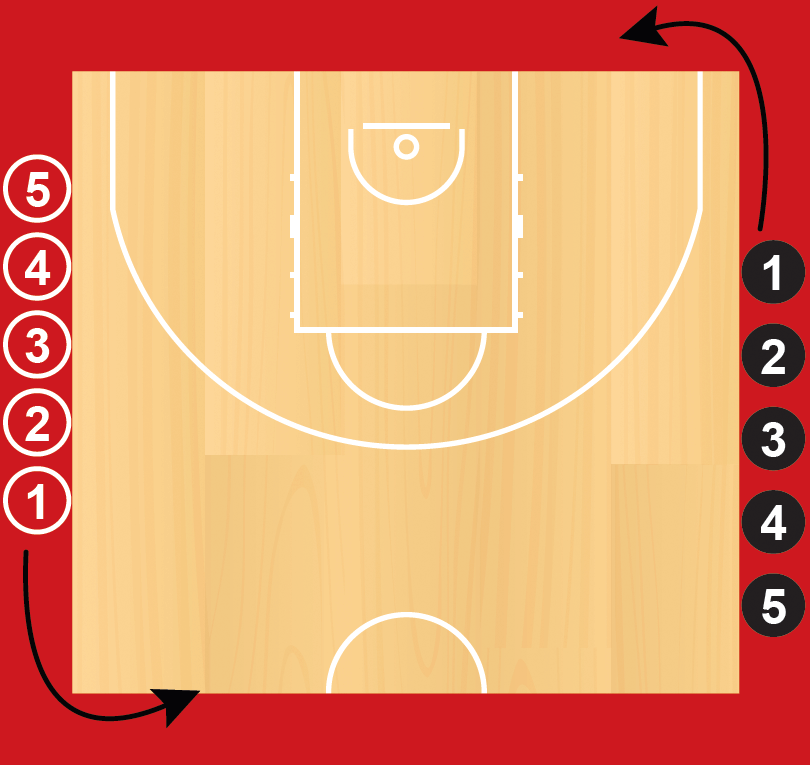

Team Pursuit

Have two teams start on opposite sides of the court or other area. They run around the designated area either for a set amount of time or specified number of laps.

All members of the team must cross the line for the team to finish. If one team overtakes the other team they automatically win. All five players must run past the five players of the other team to overtake.

Coach can either have the team run as a group (and it is up to the team to stay together) or they can run it as a “pursuit” (which is a type of race used in cycling).

In a pursuit, the coach has the teams run so that the last person in the group must sprint to get to the front. Once there, they call out and the next person sprints to the front.

Wheelbarrow Race

Athletes work in pairs. One holds their team mates legs and the team “walks” using their hands, with their chest facing the ground. It can also be done, with the athlete having their back to the ground (this is harder as it uses the tricep, which is a smaller muscle.).

Group Running

Have the athletes run whilst holding hands with one or two other athletes. It can also be done with athletes standing behind each other, holding each other at the hips.

The key with this activity is that each group can only go as fast as the slowest member. The activity is most effective when done when athletes are tired, so that the athletes are working to keep up with their team mates.

Lay-up Circuit

Athletes work in small groups (up to 5) taking a simple lay-up, rebounding their own shot and then returning to the lay-up line. Have players run around a cone, touch the sideline etc to increase the distance that they run.

You may give the group an objective (such as make 20 in a row) which should be challenging for them considering their skill level. Players may rest at the start (if there is a player shooting in front of them) but must otherwise must keep running.

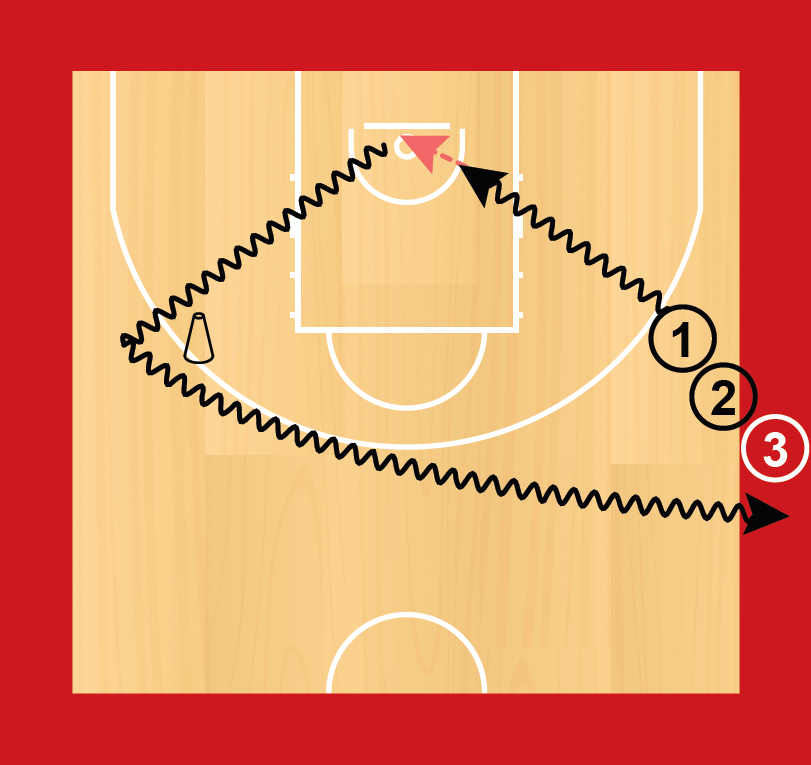

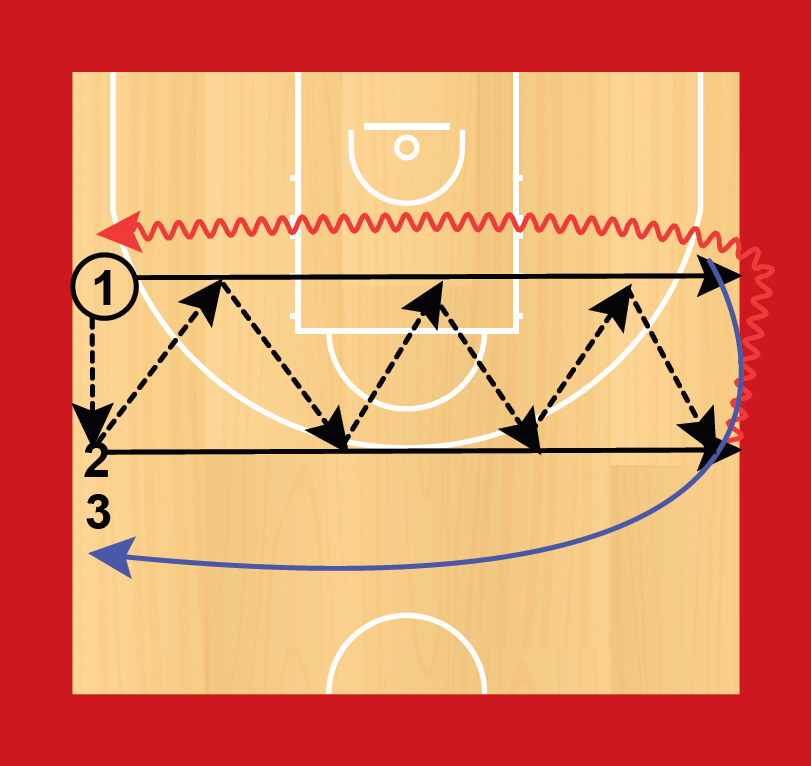

Passing Game

Athletes are in group of 3. 2 athletes pass the ball between each other as they move a specified distance. This is a rest period for the 3rd athlete.

In the diagram, 2 must dribble back to the start and commence passing with 3, whilst 1 returns to rest.

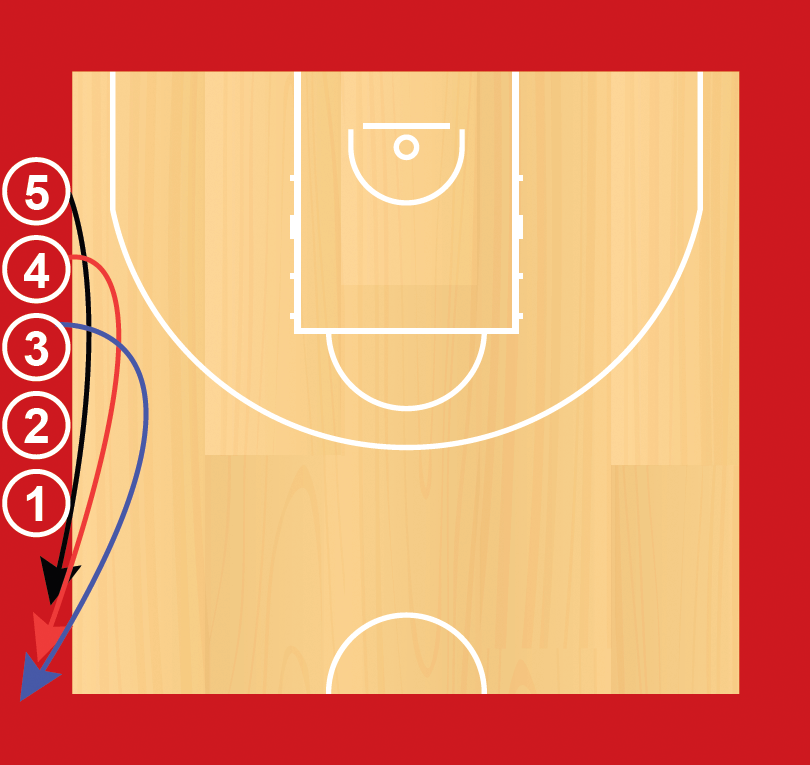

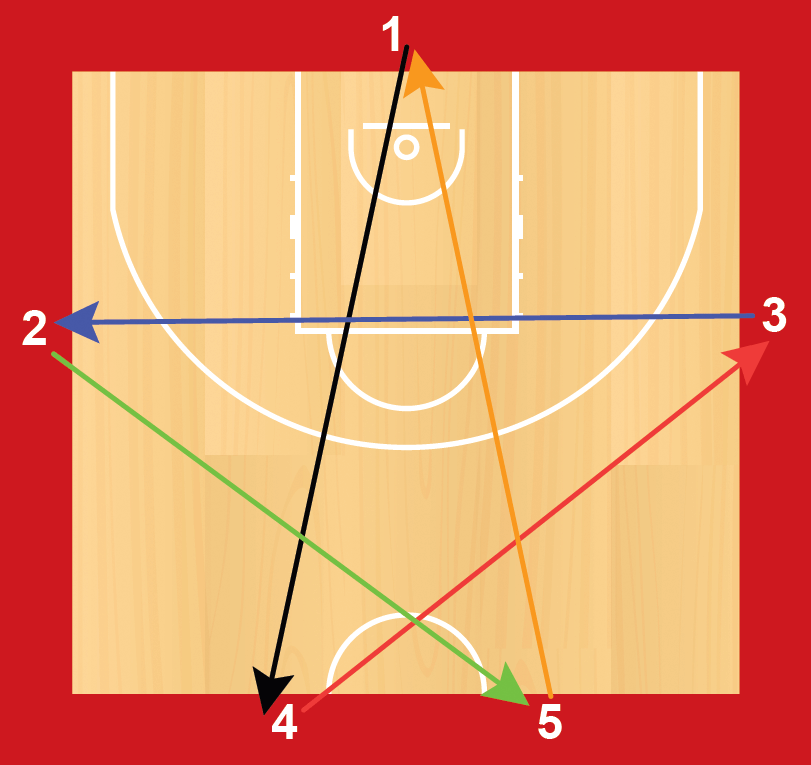

Star Runs

5 athletes sprint in a “star” formation. They must give the next team mate a “high five”.

In the diagram, 5 will do two sprints (to position 1, and then to position 4, as there will be nobody at position 1). This is deliberate to make this more difficult than the other sprints.

Coach may set a specific time to complete each sprint.

Developing the Athlete’s Mindset

Sport presents athletes (and coaches) with many situations of adversity such as losing games or missing selection to teams and sport can accordingly help athletes to learn to cope with such adversity and this can then help them in many situations outside of sport.

However, most coaches will have players that do not cope with such adversity, who put their heads down when they make a mistake or may get angry toward team mates that make mistakes. Accordingly, coaches need to be able to help their athletes to improve performance by developing a better mindset.

Getting Better by Making Mistakes

This may seem an unusual mindset to promote, but a key to coping with mistakes is to embrace the facts that:

- Every athlete will make mistakes; and

- Making mistakes is an important part of development.

For example, Magic Johnson averaged 11.2 assists per game and he averaged 3.2 turnovers per game. He also missed 6.3 field goals a game while making 6.9 field goals each game. However, his status as one of the best players of his era is undisputed. All champions are the same, they make mistakes but they learn from, rather than dwell upon, those mistakes.

| “next play”7 | Having athletes focus on the “next play” is important as that is what they can influence. What has happened cannot be changed. Athletes can use “Next” or “Next Play” as a key word. Key words are used to focus attention on what the athlete can control not the mistake they have made.

The athlete can say the word to themselves when they are having negative thoughts. Some athletes write key words on their wrist to look at when they have negative thoughts or the keyword can be used by the coach or team mates when their team mate appears focused on negative thoughts. |

| “Release” the Mistake | For some athletes having a physical “release” can help to refocus their back to the present. Two common techniques are:

Both are a physical prompt to refocus their mind and could also be used in conjunction with a key word. They can be performed quickly without affecting the play. |

| Acknowledge a Better Play | Being beaten whether in a game or a particular play only means in that game or play that the opponent was successful. It does not mean that the opponent will win the next game or play. A player can focus on the next game or play by acknowledging an opponent’s good play. An example of this is often seen in tennis, when a player will applaud the play of an opponent. |

| Focus on Small Goals | Players in a team that falls behind early by a large margin in the game may “drop their head” and see the game as lost. In this situation, the coach should identify smaller segments to focus on, not just trying to outscore the opponent by a large margin.

The segments may be trying to outscore the opponent in short periods of time (e.g. 5 minutes) or it might be process objectives such as boxing out, containing dribble penetration or scoring from a particular offensive play. Even if the team is unable to recover the large deficit, focusing on these smaller objectives can provide them with some “success” for the next game. |

| “Control the Controllable” | Coaches should emphasise with their players to keep their attention focused on those things which they can control. Whether it is the decision of a referee, an exceptional play by an opponent or a mistake that a player has made. The coach requires their players to remain focused on what they can control and the coach should similarly not be distracted by things that cannot be controlled. |

| Accept the Mistake | Players are unlikely to be able to do this unless the coach also demonstrates this. Coaches that immediately substitute players that make mistakes or berate players that make mistakes are likely to create an atmosphere where players are scared of making mistakes. Ironically, this may make them more likely to make mistakes.

When a mistake is made the coach ought to demand that athletes learn from it and avoid repeating it but not dwell on the fact that it was made. As Dean Smith reminds us: What to do with a mistake? Recognise it, admit it, learn from it, forget it. |